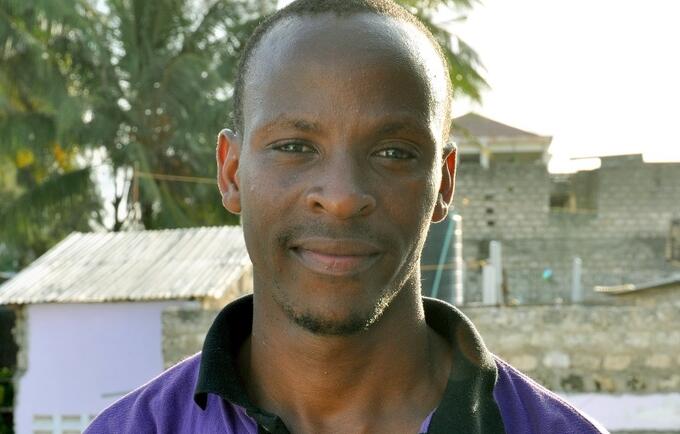

MTWAPA, Kenya – Mtwapa, a town north-east of Mombasa in the direction of Malindi, is known for its night life. Here you will find non-stop parties, day and night. But as 24-year old paralegal Joshua Mwaega will tell you, beneath the partying lies abject poverty and heart-rending cases of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

Joshua, a volunteer with Mtwapa ICRH Kenya Youth, a youth group supported by the International Centre for Reproductive Health (ICRH) and UNFPA, experienced this first hand. “As a child, we lived a really tough life because my father never went to school. We survived on one meal a day, often brought to us by my mother, who endured physical violence in addition to the hardship of caring for us,” he says.

For three years, Joshua has been working as a paralegal to support others suffering from SGBV. His work on one case in particular has had a life-changing effect – that of a 13-year old girl who was being sexually abused by a man in cahoots with her mother, in 2014.

Asha* had been given up as a house help by her mother to help the man every evening after school and on weekends. In places like Mtwapa, this is a common practice as families look for every means to make an extra shilling. This work was a smokescreen, though, as both the man and Asha’s mother knew what he really wanted.

One day, Asha’s teachers caught her and a schoolmate looking at pornographic magazines. On questioning, Asha revealed that they had been given to her by the man she worked for. Out of concern for Asha, one of the teachers who knew Joshua and his work as a paralegal called him for assistance. Further probing and an examination showed that the girl was being sexually abused on a regular basis.

A bribe to drop the case

With persistence, Joshua and Asha’s teachers managed to get the police and justice system to hear the case in court. But during a delay in this process, the accused’s lawyer made Joshua an offer: “He asked me how much our organization pays us as paralegals and said his client was ready to give us Sh. 3m (US$ 30,000) (to drop the case). He told us that the man was paying him Sh. 800,000 for defending him in court.”

If he agreed to the bribe, he and the teachers would be required to leave town with Asha, thus putting an end to the court case.

“I told him that no (amount of) money could buy justice,” he says.

Joshua could only imagine what that amount of money could do for him, an unemployed young man, and his family. And his actions in this case had not been appreciated by everyone. At one point, Asha’s mother had approached Joshua and chided him for interfering in the affairs of her family.

It took immense courage but Joshua refused to take the bait. “I told him that no (amount of) money could buy justice,” he says.

The court case proceeded and eventually, the man and Asha’s mother were both found guilty. Asha’s abuser was sentenced to 21 years in jail, while the mother received three and half years for benefitting from child mistreatment.

Just four months after beginning his jail sentence, Asha’s abuser died in jail.

High rate of child abuse

According to a 2014 Kenya Inter-Agency Rapid Assessment, the area has an adult poverty rate of 71 per cent – far exceeding the national rate of 46 per cent. Almost half of the population is below 15 years old, which means they are dependent on a relatively small population of working adults.

In the region child abuse is rampant, complicated by a high number of orphaned children and child marriages. It is estimated that eight million children, representing 40% of Kenya’s total child population, require special care and protection, according to a situation analysis performed by UNICEF in 2009. In 2007 and 2008, 67, 000 children required assistance in up to 36 categories of child protection issues countrywide, as recorded by the Department of Children Services (DCS). Half of the most common forms of abuse involve child neglect including abandonment. This is followed by physical abuse, sexual abuse (including incest), child labour, child marriage, emotional abuse, female genital mutilation (FGM), child trafficking, child abduction and child prostitution.1

Asha is one of the lucky ones. Joshua and his colleagues have managed to get her into a care centre, from where she has been able to continue with her schooling.

As for Joshua, he continues with his work as a volunteer paralegal, despite the many challenges he and other paralegals like him face: “We are volunteers, yet most of the survivors of sexual violence depend on us, and they think that NGOs pay us to work for them. A survivor may come to you to accompany him or her to the police station but they depend on you to pay money for the transport, which at times you might not have. Some cases get lost (in the system) because the survivor does not have the money needed to follow up,” he says.

Responding to sexual and gender-based violence

Supported by UNFPA Kenya, ICRH has been working in Kilifi to increase the capacity of service providers and others working in the community to prevent and respond to sexual and gender-based violence. The Centre’s work is in line with UNFPA Kenya’s priority of developing policies and programmes to increase availability of comprehensive sexuality education and sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents.

“We have been training health care providers and community-based paralegals to identify and help respond to the rampant number of cases of sexual violence,” says Nzioka King’ola, Deputy Director of ICRH.

“The world will one day reward our hard work and commitment to justice.” - Joshua Mwaega

Since January 2015, 20 paralegals from Mtwapa have been trained, while about 2000 peer educators from a targeted 4000 have been trained to provide family planning and information to youth on prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Their intervention has allowed Asha and other adolescents like her to return to their lives of attending school in the hope that they will one day be able to achieve their full potential.

For Joshua – who hopes to become an actor and later a film producer – and other unpaid paralegals like him, this activism is a calling that is driven by a passion for justice. “The world will one day reward our hard work and commitment towards finding justice for the vulnerable,” he says.

* Not her real name.